Myasthenia gravis isn’t just muscle weakness. It’s weakness that gets worse when you use your muscles-and gets better when you rest. Imagine lifting your eyelid, then having it drop again five minutes later. Or chewing your dinner, only to find your jaw too tired to finish. This isn’t laziness. It’s myasthenia gravis (MG), a rare autoimmune disorder where your body attacks the connection between nerves and muscles. The result? Fatigable weakness-the hallmark of MG-and a treatment landscape that’s changed dramatically in the last decade.

What Causes Fatigable Weakness in Myasthenia Gravis?

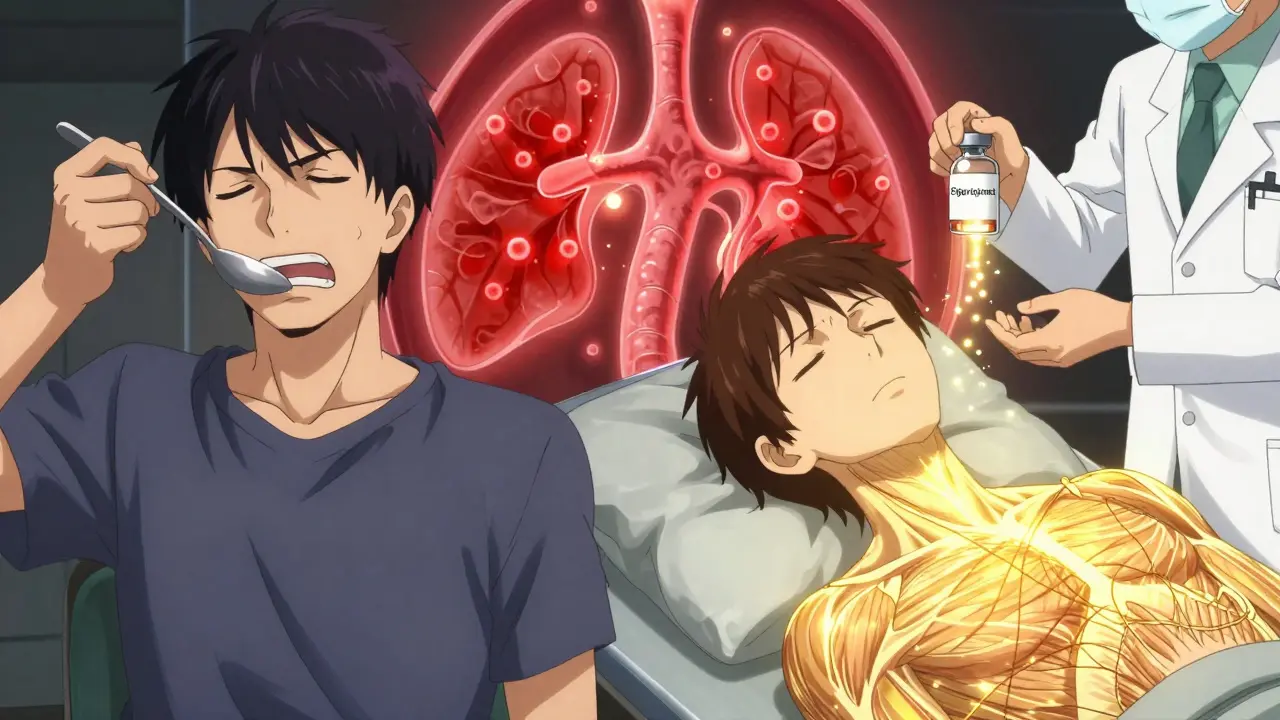

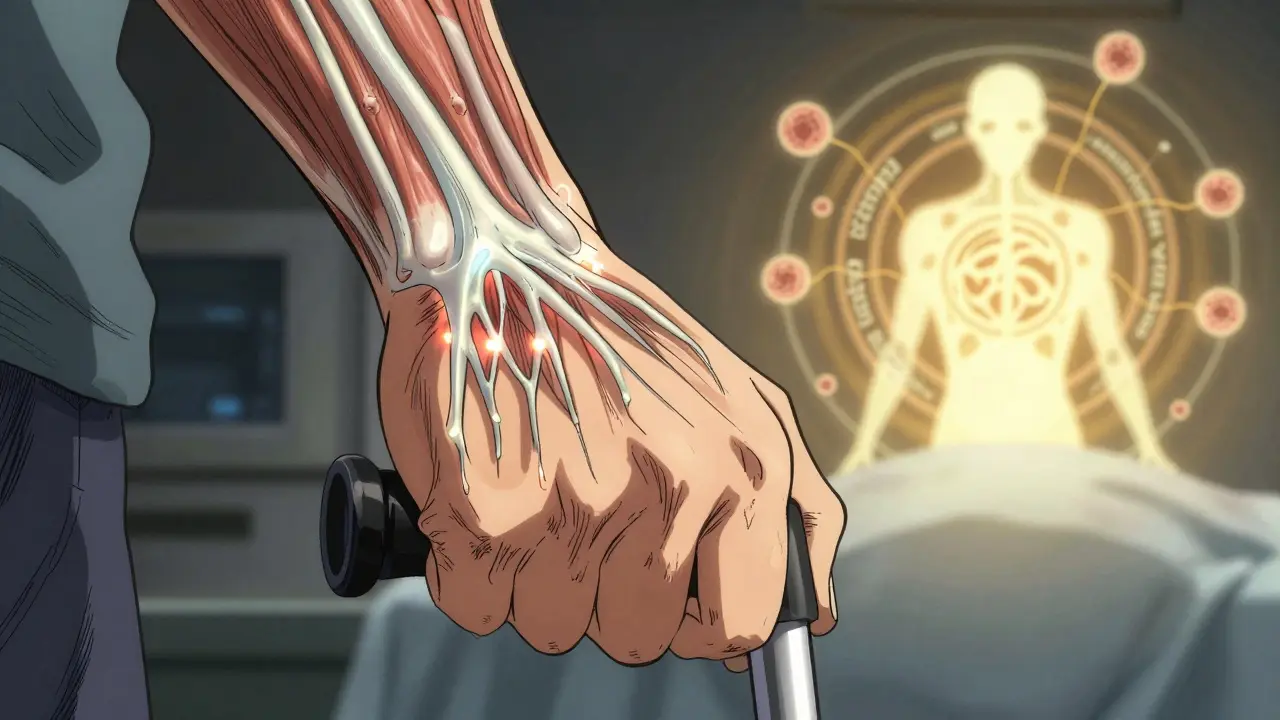

At the neuromuscular junction, nerves send signals to muscles using a chemical called acetylcholine. In MG, your immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that block or destroy the receptors for this chemical. Think of it like a broken doorbell: the bell rings (nerve sends signal), but the door doesn’t open (muscle doesn’t respond). The more you ring the bell-by moving, talking, or chewing-the weaker the response gets. Rest lets the system reset. That’s why MG symptoms vary hour to hour, day to day.

Eighty to ninety percent of people with generalized MG have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). About 5 to 8% have antibodies against something called MuSK. The rest are seronegative-no known antibodies found yet, but symptoms match perfectly. This isn’t just academic. The type of antibody you have affects how your disease behaves and what treatments work best.

Who Gets Myasthenia Gravis?

MG doesn’t pick favorites, but it does have patterns. About 65% of cases start before age 50, often in women. These early-onset cases are linked to thymic hyperplasia-an enlarged, overactive thymus gland. The other 35% develop MG after 50, more often in men, and about 10 to 15% of them have a thymoma-a tumor in the thymus. This isn’t coincidence. The thymus, a gland behind the breastbone, helps train immune cells. In MG, it seems to go rogue, teaching the immune system to attack muscle receptors.

Over 85% of people start with eye symptoms: drooping eyelids (ptosis) or double vision (diplopia). But within two years, half to 80% of those with only eye involvement will develop generalized weakness-trouble swallowing, speaking, climbing stairs, or lifting arms. The progression isn’t random. It’s predictable enough that doctors monitor closely from day one.

How Is MG Diagnosed and Measured?

Diagnosis starts with symptoms and a physical exam. The ice pack test-putting ice on a droopy eyelid-can temporarily improve it, hinting at MG. Electromyography (EMG) shows abnormal muscle response after repeated stimulation. Blood tests check for AChR or MuSK antibodies. For seronegative cases, more advanced testing like muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) or LRP4 antibody panels may be used.

Doctors track severity with the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis Score (QMGS). A score above 11 means moderate to severe disease-enough to require immunotherapy beyond just symptom relief. This isn’t guesswork. It’s a standardized tool that helps decide when to move from pyridostigmine to steroids, or when to consider plasma exchange.

First-Line Treatments: Symptom Control and Steroids

Pyridostigmine is the go-to first step. It blocks the enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine, so more of it sticks around to help muscles respond. Most people take 60 to 240 mg a day, split into doses. It helps with chewing, walking, and lifting-but doesn’t stop the immune attack. It’s like putting a bandage on a bullet wound. It helps, but it doesn’t fix the cause.

That’s where corticosteroids come in. Prednisone, at 0.5 to 1.0 mg per kg daily, is the most common immunosuppressant used. Studies show 70 to 80% of patients see major improvement or even full remission on steroids. But the trade-off? Weight gain, mood swings, high blood sugar, and bone thinning. About 70% of people on long-term prednisone over 10 mg/day gain weight. It’s effective, but harsh.

Immunosuppressants: The Long Game

Because steroids aren’t sustainable long-term, doctors add steroid-sparing drugs. Azathioprine is the classic choice. Taken daily at 2 to 3 mg per kg, it takes 12 to 18 months to work-but once it does, 60 to 70% of patients stabilize. Mycophenolate mofetil (1,000 to 1,500 mg twice daily) works faster, with 50 to 60% effectiveness. Both reduce steroid doses over time.

But not all MG is the same. If you’re MuSK-positive, azathioprine and mycophenolate often don’t cut it. Rituximab, a drug that wipes out B-cells, works far better. Studies show 71 to 89% of MuSK-positive patients reach minimal manifestation status with rituximab-compared to just 40 to 50% in AChR-positive cases. This is why antibody testing isn’t optional. It changes your entire treatment path.

Fast-Acting Rescue Therapies: IVIG and Plasma Exchange

When MG flares-when swallowing becomes impossible, or breathing gets labored-doctors need fast results. That’s where IVIG and plasma exchange (PLEX) come in. Both work within days. IVIG floods your system with healthy antibodies to confuse your immune system. PLEX literally removes your bad antibodies from your blood.

PLEX acts faster-often within 2 to 3 days-but needs a central line and carries risks like low blood pressure or infection. IVIG is safer, given through a vein over a few days, but takes 5 to 7 days to kick in. Both last 3 to 6 weeks. They’re not cures. They’re bridges-to let your body recover while slower drugs take effect.

Thymectomy: Removing the Source

For generalized AChR-positive patients between 18 and 65, removing the thymus isn’t optional-it’s standard. The MGTX trial showed thymectomy nearly doubled the chance of reaching minimal manifestation status compared to medication alone. After five years, 35 to 45% of early-onset patients go into complete remission without any drugs. That’s not rare. That’s the goal.

Thymectomy doesn’t help MuSK-positive or seronegative patients. It’s not a one-size-fits-all surgery. But for the right person, it can change everything.

The New Frontier: Targeted Immunotherapies

The biggest shift in MG treatment isn’t in steroids or surgery-it’s in drugs that target the immune system’s recycling system. Efgartigimod, approved in 2021, blocks the neonatal Fc receptor (nFcR), which normally saves IgG antibodies from being destroyed. By blocking it, the body clears out pathogenic antibodies in days. In the ADAPT trial, 68% of patients reached minimal manifestation status. No IV lines. No hospital stays. Just weekly infusions.

Ravulizumab, approved in 2023, blocks the complement system-a part of the immune system that damages muscle receptors. It’s given monthly by infusion. These drugs aren’t magic bullets, but they’re turning MG from a chronic, managed condition into one that can be actively reversed.

What Doesn’t Work-and What Can Make It Worse

Not all immune drugs are safe in MG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), used for cancer, can trigger severe MG or make existing MG explode. In one study, 60% of ICI-induced MG cases came with myocarditis. Over 80% of those patients ended up in the ICU. If you have MG and are considering cancer immunotherapy, talk to a neurologist first.

Also, avoid certain antibiotics (like fluoroquinolones and macrolides), beta-blockers, and magnesium infusions. They can worsen weakness. Even common infections can trigger a myasthenic crisis. Vaccines? Stay up to date. Flu, pneumonia, and COVID shots are strongly recommended.

Living with MG: Long-Term Management

Most people with MG need long-term treatment. Eighty-five to ninety percent stay on immunosuppressants. But remission is possible. Younger patients, especially after thymectomy, have the best shot. The key? Stay at minimal manifestation status-no symptoms, no daily limitations-for at least two years before even thinking about tapering meds. Taper too soon, and relapse hits 40 to 50% of the time.

Side effects are real. Azathioprine can hurt your liver. Steroids can break your bones. IVIG can cause headaches. But these are manageable. Regular blood tests, bone density scans, and close follow-up make all the difference. This isn’t a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition-and like diabetes or hypertension, it’s controllable.

What’s Next?

Right now, over 15 clinical trials are testing new drugs: rozanolixizumab, inebilizumab, and next-gen nFcR blockers. The goal? Disease modification without lifelong immunosuppression. The dream? A cure. The reality? We’re closer than ever. MG is no longer just about managing symptoms. It’s about resetting the immune system-and for many, that’s already working.

Is myasthenia gravis hereditary?

No, myasthenia gravis is not inherited. It’s an autoimmune disorder, not a genetic disease. While some people may have genes that make them more prone to autoimmune conditions, MG itself isn’t passed down from parent to child. However, having a family history of other autoimmune diseases like lupus or thyroiditis might slightly increase your risk.

Can you die from myasthenia gravis?

With modern treatment, death from MG is rare. The biggest risk is a myasthenic crisis-when breathing muscles become too weak, requiring emergency ventilation. This happens in about 15 to 20% of people at some point. But with prompt care in an ICU, survival rates are over 95%. The key is recognizing early signs: trouble swallowing, slurred speech, or shortness of breath even at rest. Don’t wait.

Does myasthenia gravis affect the heart?

MG primarily affects skeletal muscles, not the heart. Heart muscle uses a different type of receptor, so it’s usually spared. But there’s one major exception: immune checkpoint inhibitors used in cancer can trigger a rare, severe form of MG that often includes myocarditis (heart inflammation). In these cases, heart involvement can be life-threatening. For standard MG, heart rhythm or function is typically unaffected.

Can pregnancy make myasthenia gravis worse?

Pregnancy can be unpredictable in MG. About one-third of women worsen during pregnancy, one-third improve, and one-third stay the same. The biggest concern is neonatal myasthenia-a temporary condition in newborns caused by maternal antibodies crossing the placenta. Symptoms like weak cry or poor sucking usually resolve in days to weeks. With careful planning and monitoring, most women with MG have healthy pregnancies and babies.

Is there a cure for myasthenia gravis?

There’s no universal cure yet, but remission is possible. Around 35 to 45% of early-onset AChR-positive patients who have a thymectomy reach complete, drug-free remission after five years. New drugs like efgartigimod are showing we can reverse antibody damage. The goal now isn’t just symptom control-it’s restoring immune balance. For many, that’s already happening.

Medications

Medications

Ernie Simsek

February 12, 2026 AT 21:24