Dose Adjustment Calculator

Calculate Your Dose Adjustment

This tool helps calculate adjusted medication doses based on renal function using the Cockcroft-Gault equation. Critical for Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs.

How to use: Enter the patient's age, weight, serum creatinine level, and gender. Select the drug type (NTI or non-NTI). The calculator will determine the appropriate dose adjustment based on renal function.

This tool is for educational purposes only. Always consult with a healthcare professional for actual clinical decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Understand the therapeutic index to spot drugs that need tight dosing.

- Use kidney, liver, age, weight, and genetics to personalize the dose.

- Set a clear monitoring schedule - labs, symptoms, and timing matter.

- Leverage decision‑support tools or pharmacist‑led programs to reduce errors.

- Watch for red‑flags like missed doses, interacting meds, and lab outliers.

Medication dose adjustment is a clinical practice that tweaks the amount of a drug to keep it effective while steering clear of side effects. The goal is simple: get the sweet spot between benefit and risk. Over the last few decades, the concept has moved from a vague “adjust as needed” rule to a data‑driven process called precision dosing.

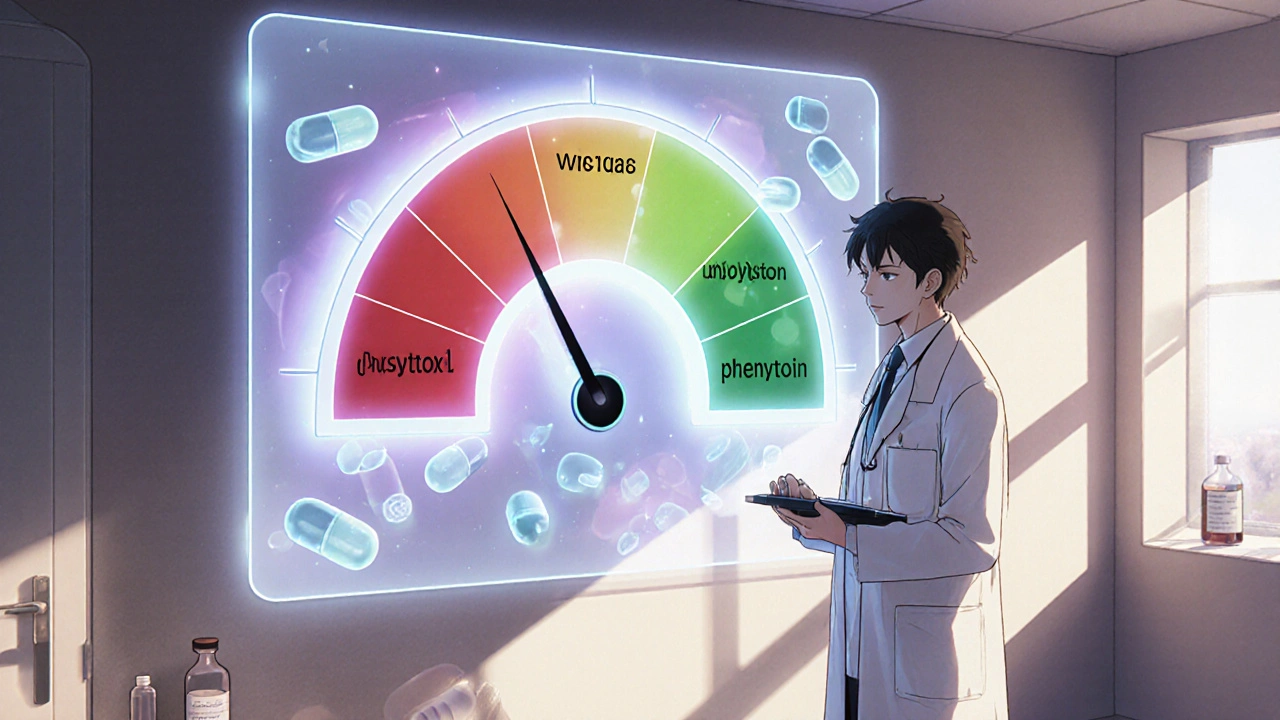

When you hear the term therapeutic index, think of it as a safety gauge. A high index (>10) means the drug is forgiving; a low index (≤3) signals a narrow window where a small change can swing you from cure to toxicity. That’s why drugs like warfarin, digoxin, and phenytoin demand extra vigilance.

Understanding the Therapeutic Index

Therapeutic index = toxic dose ÷ effective dose. For a drug with an index of 2, the toxic dose is only twice what you need to see a response. That’s the reality for many NTI drugs (Narrow Therapeutic Index). Miss a dose, add a new medication, or let kidney function dip, and you could tip into dangerous territory.

Historical milestones matter. Early 20th‑century researchers like A.J. Clark mapped dose‑response curves, but it wasn’t until the 1962 Kefauver‑Harris Amendments that regulators demanded efficacy proof, paving the way for today’s dose‑adjustment protocols.

Patient‑Specific Factors that Shape the Dose

One size never fits all. The most common variables include:

- Renal function - measured by creatinine clearance or eGFR. Many drugs are cleared mainly by the kidneys, so a drop in clearance means a lower dose.

- Hepatic function - scores like Child‑Pugh or MELD guide dosing for drugs metabolized by the liver.

- Body size - ideal body weight vs. actual weight, especially in obesity, changes the volume of distribution.

- Age - geriatric patients often need a 20‑30% reduction because metabolism slows.

- Genetics - pharmacogenomics (e.g., CYP2D6 variants) affect up to a quarter of common drugs.

Combine these factors in a systematic way. For example, an elderly patient with a creatinine clearance of 45 mL/min, weighing 90 kg, and carrying a CYP2C19*2 allele may need a 30‑40% dose cut for a drug like clopidogrel.

Step‑by‑Step Guide to Adjusting a Dose

- Gather baseline data - labs, weight, age, liver/kidney scores, medication list, and any known genetic results.

- Identify if the drug is an NTI drug. If yes, schedule therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM).

- Calculate the initial adjustment using the most relevant factor. For renal dosing, apply the Cockcroft‑Gault equation: Creatinine Clearance = ((140‑age) × weight) / (72 × serum creatinine) × 0.85 for females.

- Prescribe the new dose and set a monitoring interval - often 1‑2 weeks for NTI drugs, longer for stable non‑NTI agents.

- Review lab results (peak/trough levels for TDM) and clinical response. Adjust up or down in 10‑20% increments.

- Document the change, explain it to the patient, and provide a clear “what‑to‑do‑if‑you‑miss‑a‑dose” plan.

Throughout, keep the dose adjustment focus on both efficacy signs (symptom relief, disease markers) and safety signs (labs, new symptoms, adverse events).

Tools, Technologies, and Support Systems

Manual calculations are error‑prone. Modern clinics rely on:

- Clinical decision‑support systems (CDSS) that pull labs, weight, and genetics into an algorithm.

- Pharmacist‑led anticoagulation clinics - studies show a 60% drop in major bleeding for warfarin users when pharmacists manage dosing.

- Precision‑dosing platforms such as InsightRX or DoseMe - they apply population PK models to individual data.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring labs that provide rapid peak/trough reports.

Adopting any of these reduces the odds of a dosing mistake by roughly a third, according to recent meta‑analyses.

Comparison: NTI vs. Non‑NTI Drugs

| Aspect | NTI Drugs | Non‑NTI Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic index | ≤3 (often 2‑3) | >10 |

| Typical monitoring | Therapeutic drug monitoring (peak/trough levels) | Symptom‑based, occasional labs |

| Common examples | Warfarin, digoxin, phenytoin, tacrolimus | Penicillin, acyclovir, ibuprofen |

| Risk of toxicity from small dose change | High - can be fatal | Low - usually mild side effects |

| Impact of renal/hepatic impairment | Significant - dose must be adjusted | Variable - many have wide safety margins |

Common Pitfalls & Pro Tips

Pitfall: Relying on the label dose without checking patient‑specific labs. Tip: Always cross‑check the latest creatinine, liver enzymes, and any recent drug‑interaction alerts before refilling.

Pitfall: Ignoring missed doses. Tip: Give patients a clear action plan - e.g., “if you’re more than 12 hours late, take half the missed dose, then resume normal schedule.”

Pitfall: Overlooking polypharmacy interactions. Tip: Use a CDSS that flags CYP450 inhibitors/inducers and prompts dose reduction ranges (often 25‑50%).

Pitfall: Adjusting based on a single lab value. Tip: Look at trends - three consecutive INR readings, or serial trough levels, before making a jump.

Real‑World Case Snapshots

Case 1 - Elderly warfarin user: 78‑year‑old with creatinine clearance 48 mL/min, INR drifting to 4.2. The pharmacist reduced the weekly dose by 15% and scheduled INR checks every 5 days. Within two weeks the INR stabilized at 2.7 and no bleeding events occurred.

Case 2 - Digoxin in a patient with fluctuating potassium: A 65‑year‑old on diuretics experienced occasional low potassium. The clinician added a potassium supplement and lowered digoxin by 25%, then monitored digoxin troughs weekly. Toxicity signs vanished, and cardiac function improved.

Case 3 - Precision dosing software for tacrolimus: A transplant clinic integrated an AI‑driven dosing platform that considered weight, genetics, and liver function. Dose errors dropped 40% and graft rejection rates fell by 12% over a year.

Next Steps for Clinicians and Patients

1. Audit your current medication list - spot any NTI drugs.

2. Set up a regular lab calendar (e.g., INR, trough levels, renal panels).

3. Talk to a pharmacist about enrolling in a dose‑management program.

4. If genetics are available, request CYP450 testing for high‑risk meds.

5. Document every change in the electronic health record with the reason and monitoring plan.

When should I consider adjusting a medication dose?

Any time you see a lab out of range, a new symptom, a change in kidney or liver function, or when a new interacting drug is added. For NTI drugs, even small changes in these parameters trigger a review.

How often should therapeutic drug monitoring be done?

Initially after a dose change, draw a peak level 1‑2 hours post‑dose and a trough just before the next dose. Repeat every 1‑2 weeks until stable, then space out to monthly or quarterly based on the drug’s half‑life and patient stability.

Can I adjust my own dose if I miss a pill?

Only if your prescriber gave you a clear missed‑dose plan. A common rule is: take half the missed dose if it’s been more than 12 hours, otherwise take the full dose and continue as scheduled. Never double up.

What role does genetics play in dose adjustment?

Genetic variants in enzymes like CYP2D6, CYP2C19, or CYP3A4 can speed up or slow down drug metabolism. Knowing a patient’s genotype lets you pre‑emptively lower or raise the dose, reducing trial‑and‑error.

Are there any free tools for dose calculation?

Many hospital EHRs embed calculators for creatinine clearance and weight‑based dosing. Online, the FDA’s dosing calculator and open‑source tools like MedCalc provide basic formulas at no cost.

Medications

Medications

Olivia Harrison

October 24, 2025 AT 19:12When you’re pulling a new chart, grab the most recent labs first and note the creatinine, liver enzymes, and any recent trough levels. Then match those numbers to the drug’s clearance pathway – kidneys for most antibiotics, liver for many antivirals. A quick 10‑20 % dose tweak based on the Cockcroft‑Gault result can keep the drug in the therapeutic window without a full‑blown trial‑and‑error run. Don’t forget to explain the change to the patient in plain language; a clear “what‑to‑do‑if‑you‑miss‑a‑dose” plan reduces anxiety and errors.

ram kumar

November 1, 2025 AT 20:39Alas, the tragedy of the dosage mis‑calculation! In a world where a 0.5 mg slip can turn a life‑saving anticoagulant into a bleeding time‑bomb, we must treat each prescription like a tightrope act. The drama unfolds whenever a new lab arrives, and the hero‑doctor must recalibrate before the next dose. Ignoring that drama is a plot twist nobody wants.

Charlie Stillwell

November 9, 2025 AT 23:05🔬 Leveraging population PK models via platforms like InsightRX offers a Bayesian updating mechanism that refines individual Bayesian priors with each new trough – essentially turning static dosing into a dynamic, data‑driven algorithm. The integration of CYP2C19 genotype data adds another layer of precision, shaving off up to 30 % of adverse events in high‑risk cohorts. 👍🏽 Embrace the tech, or you’ll be stuck in the era of guesswork.

Tamara Tioran-Harrison

November 18, 2025 AT 01:32Oh, because dosing is just a guessing game, isn’t it? :)

kevin burton

November 26, 2025 AT 03:59A quick way to remember the renal dosing formula is “140 minus age, times weight, divided by 72 times serum creatinine, with a 0.85 factor for females.” Plug the numbers in, round to the nearest 5 mL/min, and you have a solid creatinine‑clearance estimate to guide dose reductions.

Max Lilleyman

December 4, 2025 AT 06:25Exactly, and don’t forget to double‑check the units – milligrams versus micrograms can make a world of difference.

Buddy Bryan

December 12, 2025 AT 08:52Your point about PK models is spot on; they turn sparse lab data into a continuously updating dose recommendation, which is a game‑changer for NTI drugs.

Jonah O

December 20, 2025 AT 11:19Therapautic indxe is just a tool, not a crystal ball – if you misread it you might end up over‑dosing the patient.

Brett Witcher

December 28, 2025 AT 13:45One must acknowledge the historical context in which therapeutic indices were first quantified; the early pharmacologists employed rigorous dose‑response curves that laid the groundwork for today’s precision dosing paradigms.

Benjamin Sequeira benavente

January 5, 2026 AT 16:12Let’s all commit to using clinical decision‑support systems for every NTI medication; the evidence shows a 60 % drop in major bleeding when pharmacists manage warfarin dosing, so why settle for less?

Shannon Stoneburgh

January 13, 2026 AT 18:39Precision dosing isn’t a buzzword, it’s a practical necessity in everyday practice. When a patient presents with fluctuating kidney function, the dose you wrote yesterday may be too high today. Simple bedside calculators can give you a ballpark estimate, but they don’t replace regular lab monitoring. Checking a trough level a week after a change lets you see whether the drug is creeping toward toxicity or staying comfortably within range. If the level is off, adjust by no more than 10‑20 % and re‑measure. Remember that genetics can shift metabolism; a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer may need a lower dose even if labs look normal. Communication with the patient is key – a written plan for missed doses prevents accidental double‑dosing. Documentation in the electronic health record should include the reason for the change, the calculation used, and the follow‑up schedule. Pharmacists are valuable allies; they can double‑check calculations and flag drug‑drug interactions that you might miss in a busy clinic. If you have access to a CDSS, let it run the numbers and alert you to outliers. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, even a small dietary change can affect serum levels, so counsel patients on consistent intake. Over‑reliance on a single lab value can be misleading; trends over three consecutive readings are far more reliable. When in doubt, consult the latest guidelines or a specialist. The ultimate goal is to keep the patient stable, symptom‑free, and out of the hospital. By integrating labs, genetics, and patient education, you build a safety net that catches dosing errors before they cause harm.