When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, two types of generics can rush in - and only one is truly fighting for lower prices.

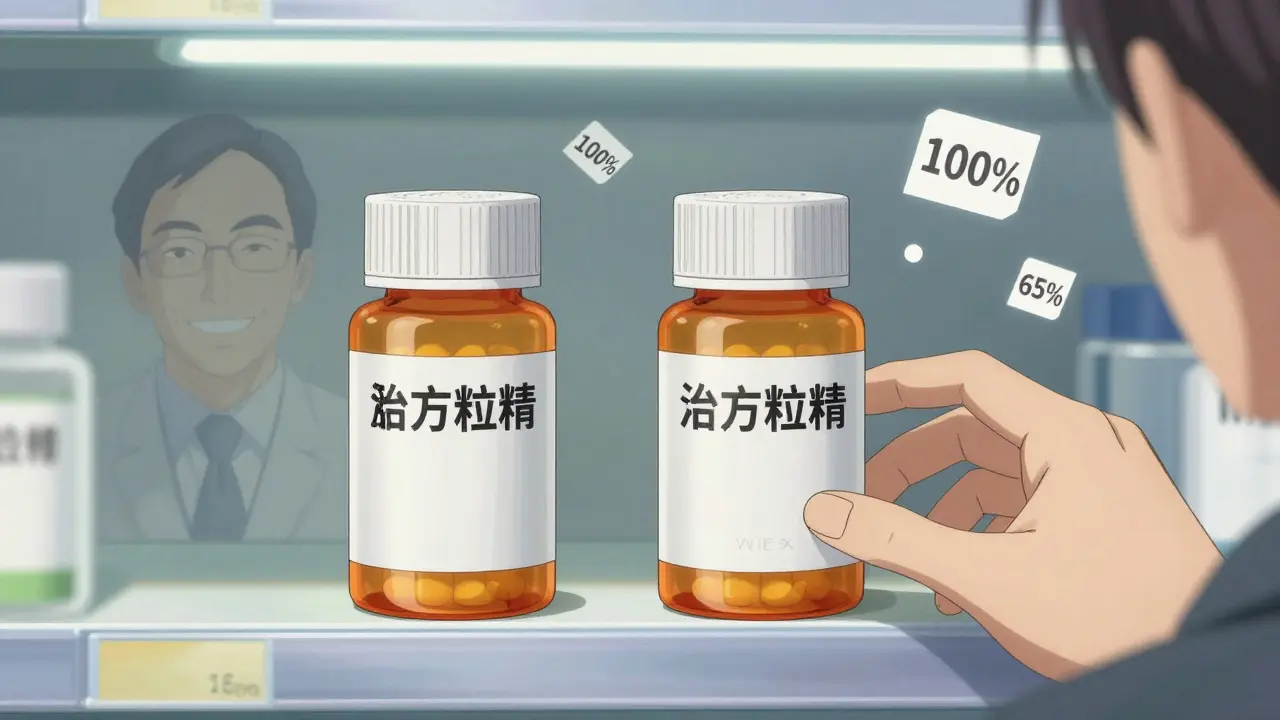

If you’ve ever picked up a prescription and seen a generic version with the same name as the brand drug - but cheaper - you’ve seen the power of generic competition. But not all generics are created equal. There’s a hidden layer in the drug market that most patients never see: the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic. And when they hit the market at the same time, it changes everything - especially how much you pay.

The U.S. generic drug system was built on a promise: reward the first company brave enough to challenge a patent, give them 180 days of exclusive sales, and let lower prices flood the market. That’s the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. But over the last decade, brand-name drugmakers have learned how to game the system. They don’t wait for the generic to arrive. They launch their own version - an authorized generic - on the same day. And suddenly, the first generic isn’t winning. It’s being split in half.

What’s a first generic, really?

A first generic is the first company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA after a brand-name drug’s patent expires. This company has to prove its version works the same way as the original - same active ingredient, same dosage, same effect. It’s not easy. They often spend years in court fighting patent lawsuits. They invest $5 million to $10 million per drug. And if they win, they get 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. No competition. No price drops from other generics. Just them.

During that 180-day window, they usually capture 70% to 90% of the market. For a blockbuster drug like Lyrica (pregabalin), that meant Teva, the first generic maker, expected to make over $300 million in revenue. That’s the whole point of the law: reward the risk-taker, drive prices down fast.

What’s an authorized generic? And why does it feel like cheating?

An authorized generic isn’t a new drug. It’s the brand-name drug - same factory, same formula, same packaging - but sold under a generic label. No ANDA needed. No bioequivalence studies. No waiting for FDA approval. The brand company just prints a new label and ships it out.

Here’s the twist: the brand company doesn’t have to wait for the first generic to launch. They can release their authorized generic on the exact same day. And when they do, they’re not competing as a brand anymore. They’re competing as a generic. But they’ve got the advantage: they already have distribution deals with pharmacies, relationships with insurers, and years of marketing muscle.

In 2019, Pfizer launched its authorized generic of Lyrica through Greenstone LLC - the same day Teva’s generic hit shelves. Within weeks, Pfizer’s version grabbed 30% of the market. Teva’s share dropped from 90% to 60%. The price didn’t fall as hard. Patients saved less. The system didn’t work as intended.

Why timing matters more than you think

The FDA takes about 10 months on average to approve a first generic. That’s long. But an authorized generic? It can be ready in days. All the brand company needs is the green light from the patent court. Once that happens, they flip a switch.

Research from Health Affairs shows that 73% of authorized generics launch within 90 days of the first generic. More than 40% launch on the same day. That’s not coincidence. That’s strategy.

Brand companies don’t wait to see if the first generic will succeed. They attack before the first generic even has time to build momentum. And it works. Instead of prices dropping 80-90%, they only drop 65-75%. That difference costs the healthcare system billions every year.

It’s especially common in high-revenue areas: heart drugs, brain meds, diabetes treatments. Eliquis and Jardiance are two current battlegrounds where brand companies are already preparing their authorized generic launch plans.

Who wins? Who loses?

Let’s break it down:

- Brand companies win. They keep market share. They keep profits. They avoid the full price collapse that comes with true generic competition.

- First generic companies lose. They spent millions on litigation and regulatory filings. They expected a monopoly. Instead, they get a shared market and a fraction of the revenue.

- Payers and patients lose. Prices don’t drop as much. Insurance companies pay more. Patients pay more out-of-pocket. The savings promised by the Hatch-Waxman Act never fully arrive.

- Authorized generics don’t really help. They’re not independent competitors. They’re brand drugs in disguise. They don’t bring new innovation. They don’t lower costs the way true generics do.

The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) argues that authorized generics increase competition. But that’s misleading. True competition means multiple independent companies making the same drug. An authorized generic is just one company - the brand - splitting its own product into two labels.

What’s being done about it?

Regulators are starting to notice.

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act made it clear: authorized generics don’t count as real generics when it comes to Medicare drug price negotiations. That’s a big deal. It means the government won’t pretend they’re lowering prices the same way a true generic would. It’s a small step, but it’s recognition that the system is broken.

The FTC has also cracked down on "pay-for-delay" deals - where brand companies pay generic makers to delay their launch. But authorized generics are legal. They’re a loophole, not a violation. And until Congress closes it, they’ll keep being used.

Some generic manufacturers are adapting. Instead of betting everything on one drug, they’re building portfolios. They’re launching multiple generics at once. They’re moving into harder-to-make drugs - injectables, inhalers - where authorized generics are harder to copy. But for the average pill, the deck is still stacked.

The bottom line: authorized generics aren’t the hero they’re sold as

If you want lower drug prices, you need real competition. Not a brand company pretending to be a generic. Not a company that didn’t invest in the patent fight. Not a version made in the same factory as the original.

The first generic is the real challenger. The one who took the risk. The one who forced the system to change. The authorized generic? It’s a shield - not a sword.

Patients deserve the full price drop the law promised. And until authorized generics are treated for what they are - a tactic to protect profits - that promise will stay broken.

What happens next?

By 2027, authorized generics could make up 30% of all generic prescriptions - up from 18% in 2022. That means more brand companies will use this trick. More first generics will see their profits slashed. More patients will pay more than they should.

It’s not about complexity. It’s about fairness. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to break monopolies. Instead, it’s being used to extend them.

The next time you see a generic version of a brand drug - check the label. If it’s made by the same company as the brand? You’re not getting the full discount. You’re getting the brand’s version of a discount.

Medications

Medications

Linda O'neil

January 28, 2026 AT 03:04My pharmacist told me to check the manufacturer code-turns out my 'generic' was made by the same company as the brand. I felt cheated.