Opioid Nausea Management Advisor

Identify Your Nausea Type

Select the symptom pattern that best matches your experience:

Medication Check

Enter your current medications to check for dangerous interactions:

When you start taking opioids for pain, nausea isn’t just an annoyance-it’s one of the top reasons people stop taking them. Studies show 20 to 33% of patients experience opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV), and many would rather endure more pain than deal with it. That’s not just discomfort; it’s a barrier to effective treatment. The good news? You don’t have to suffer through it. But the wrong antiemetic, given at the wrong time, can do more harm than good.

Why Opioids Make You Sick

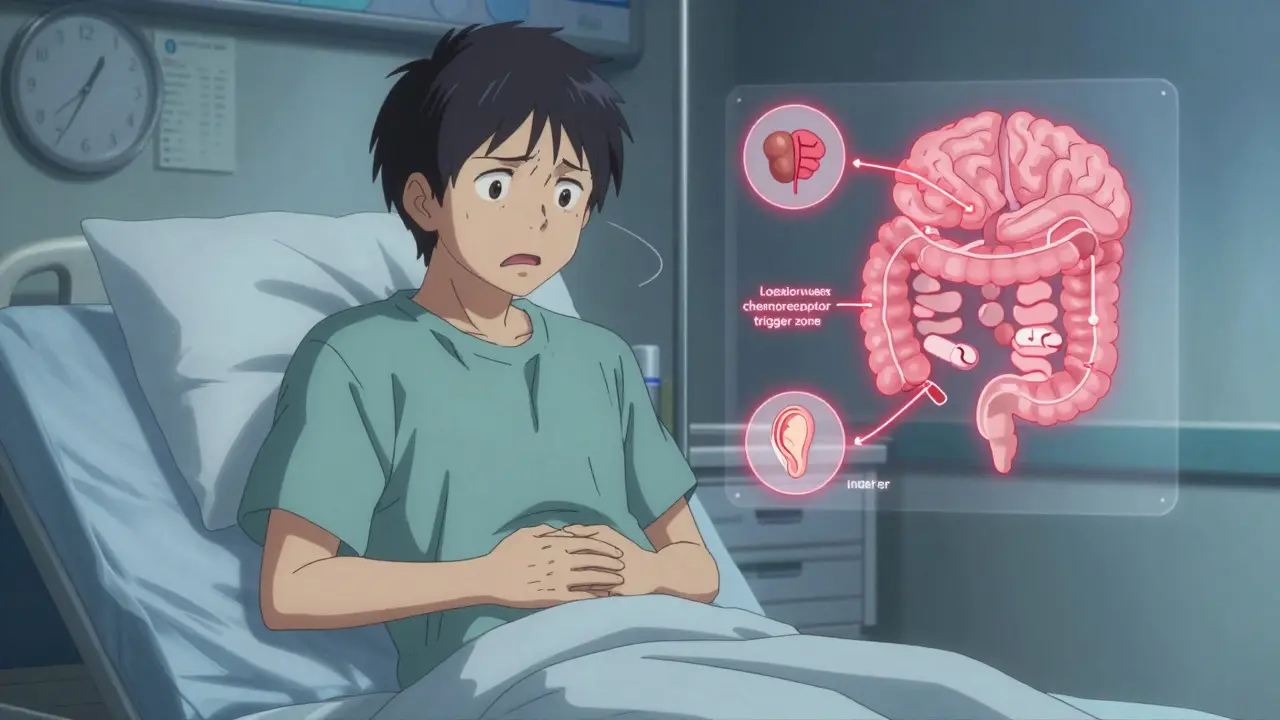

Opioids trigger nausea through multiple pathways. They slow down your gut, which can make you feel full and queasy. They also activate the chemoreceptor trigger zone in your brain-a region packed with dopamine receptors. When opioids bind there, your body thinks something’s poisoned you and tries to expel it. Some opioids also increase sensitivity in your inner ear, making you dizzy or nauseated when you move. This isn’t just one problem-it’s a mix of gut, brain, and balance systems going haywire.That’s why a one-size-fits-all antiemetic doesn’t work. If your nausea comes from gut slowdown, a prokinetic like metoclopramide might help. If it’s from brain stimulation, a serotonin blocker like ondansetron is better. And if it’s dizziness from movement, scopolamine patches or meclizine are the go-to choices.

The Myth of Routine Antiemetic Prophylaxis

For years, many doctors gave antiemetics upfront-just in case. But recent evidence says that’s often unnecessary. A 2022 Cochrane review analyzed three studies where patients received metoclopramide before IV opioids. The result? No reduction in nausea, vomiting, or need for rescue meds. Not a single study showed benefit. And that’s not because metoclopramide is weak-it’s because giving it before symptoms appear doesn’t match how OINV works.Here’s the reality: most people develop tolerance to opioid-induced nausea within 3 to 7 days. That means if you’re starting a new opioid, you’re likely to feel sick for a few days, then it fades. That’s why experts now recommend waiting. Don’t prescribe an antiemetic on day one unless nausea is already severe or you’re treating someone at high risk-like older adults or those with a history of motion sickness.

Which Antiemetics Actually Work?

Not all antiemetics are created equal. Here’s what the data says about the most common options:- Ondansetron (Zofran): Blocks serotonin receptors in the gut and brain. Effective for established OINV. Studies show 8 mg and 16 mg doses work well. But it can prolong the QT interval-especially in people with heart conditions or on other QT-prolonging drugs.

- Palonosetron (Aloxi): A newer, longer-acting 5-HT3 blocker. One study found only 42% of patients on palonosetron had nausea vs. 62% on ondansetron. It’s more expensive but may be worth it for longer-term use.

- Metoclopramide (Reglan): A dopamine blocker and prokinetic. Despite being used for decades, the latest evidence shows it doesn’t prevent OINV when given prophylactically. It can cause drowsiness, restlessness, and rarely, muscle spasms.

- Droperidol: Powerful dopamine blocker. Very effective, but carries a black box warning for QT prolongation and sudden cardiac death. Avoid unless absolutely necessary and under close monitoring.

- Scopolamine patches: Best for vestibular nausea-dizziness when moving. Place behind the ear 4 hours before opioid dose. Lasts up to 72 hours. Good for patients who feel nauseated when standing or walking.

- Meclizine (Antivert): An antihistamine. Mild sedation but safe for most. Works well for motion-sickness-type nausea. Often overlooked but useful in older adults.

There’s no perfect drug. But choosing based on the likely cause of nausea makes a big difference. If the patient says, “I feel sick when I stand up,” go with scopolamine. If they say, “I just feel like throwing up, no matter what I do,” try ondansetron.

Big Risks You Can’t Ignore

Mixing opioids with antiemetics isn’t just about nausea-it’s about safety. Both classes affect the central nervous system. Combine them with other depressants-alcohol, benzodiazepines, sleep meds-and you increase the risk of slowed breathing, coma, or death.There’s another hidden danger: serotonin syndrome. Opioids like tramadol, fentanyl, and methadone can increase serotonin. So can many antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs) and migraine drugs (triptans). When these mix, you can get high fever, rapid heart rate, muscle rigidity, and confusion. It’s rare but life-threatening. Always check a patient’s full med list before starting any opioid.

The FDA has issued warnings about these interactions. Drug labels now require updates for all opioid prescriptions. This isn’t theoretical-it’s a real, documented risk that’s caused ER visits and deaths.

What to Do Instead: A Practical Approach

Forget giving antiemetics on day one. Here’s a better plan:- Start low, go slow. Use the lowest effective opioid dose. For example, morphine at 1 mg twice daily for chronic pain can be enough. Higher doses don’t always mean better pain control-just more side effects.

- Wait and watch. If nausea appears, assess it. Is it worse when standing? Try scopolamine. Is it constant? Try ondansetron. Don’t assume it’s the opioid’s fault-could be dehydration, infection, or another drug.

- Rotate opioids if needed. Some people get nauseated on oxycodone but not on morphine. Others tolerate tapentadol better than oxymorphone. Studies show oxymorphone has 60 times higher nausea risk per dose than oxycodone. Switching can be more effective than adding a new drug.

- Use non-drug options. Ginger supplements (1 gram daily) have shown modest benefit in some studies. Acupressure wristbands (like Sea-Bands) work for motion sickness and may help some opioid-related nausea. Hydration and small, bland meals help too.

- Educate patients. Tell them: “You might feel sick for a few days. That’s normal. If it gets worse, call us. Don’t take extra pills without checking.” Most patients feel better when they know what to expect.

When to Refer or Reassess

If nausea lasts beyond a week despite trying the right antiemetic, something else is going on. Consider:- Is the patient on multiple CNS depressants?

- Are they dehydrated or constipated? (Constipation worsens nausea.)

- Could it be a metabolic issue-kidney or liver failure?

- Are they on an opioid that’s known for high nausea risk, like oxymorphone?

Don’t keep adding antiemetics. That’s not solving the problem-it’s masking it. If the nausea doesn’t improve, consider switching opioids or exploring non-opioid pain options like gabapentin, physical therapy, or nerve blocks.

The Bottom Line

Opioid-induced nausea is common-but it’s not inevitable. You don’t need to start every patient on an antiemetic. In fact, routine use is outdated. The smarter approach is to wait, observe, and treat based on symptoms. Pick the right antiemetic for the right cause. Avoid dangerous combinations. And remember: most nausea fades in less than a week. Your goal isn’t to eliminate every uncomfortable feeling-it’s to help patients stay on their pain treatment safely.Can I take ondansetron with opioids safely?

Yes, but with caution. Ondansetron can prolong the QT interval, and so can some opioids like methadone and fentanyl. If the patient has heart disease, low potassium, or is on other QT-prolonging drugs (like certain antibiotics or antidepressants), this combo increases the risk of dangerous heart rhythms. Always check an ECG if you’re unsure. For most healthy adults, a single dose of ondansetron is safe and effective for opioid nausea.

Why is metoclopramide not recommended for opioid nausea anymore?

Because studies show it doesn’t prevent nausea when given before opioids. Three clinical trials found no benefit in reducing vomiting, nausea, or need for rescue meds. It also has side effects like drowsiness and muscle spasms. While it’s still useful for gastric emptying issues, it’s not the go-to for opioid-induced nausea. Better options exist.

How long does opioid-induced nausea last?

For most people, nausea improves within 3 to 7 days as the body develops tolerance to the emetic effects. This is why short-term antiemetic use is often enough. If nausea persists beyond a week, it’s likely due to another cause-like constipation, another medication, or an underlying illness-and needs reevaluation.

Are there natural ways to reduce opioid nausea?

Yes. Ginger (1 gram daily) has been shown in studies to reduce nausea in cancer patients on opioids. Acupressure wristbands (like Sea-Bands) help with motion-sickness-type nausea. Staying hydrated, eating small bland meals, and avoiding strong smells can also help. These aren’t replacements for medication, but they can reduce the need for it.

What’s the safest opioid for someone prone to nausea?

Tapentadol has a lower risk of nausea per dose compared to oxycodone-about 3 to 4 times lower. Oxymorphone has the highest risk-60 times higher than oxycodone. Morphine and hydromorphone are moderate. If nausea is a major concern, starting with tapentadol or morphine is often a better choice than oxycodone or oxymorphone.

Can antiemetics make opioid pain relief worse?

No, antiemetics don’t reduce opioid pain relief. But some, like droperidol or high-dose metoclopramide, can cause drowsiness or confusion, which may be mistaken for reduced pain control. The real issue is drug interactions-mixing opioids with other CNS depressants can lower breathing and heart rate, which is dangerous. Always check for interactions before prescribing.

Medications

Medications

Siobhan K.

December 20, 2025 AT 22:50Finally, someone who gets it. No more blanket antiemetic prescriptions like we’re treating a toddler with a tummy ache. OINV isn’t a bug-it’s a feature of opioid pharmacology, and treating it like a one-size-fits-all problem is medical laziness.

Metoclopramide? Sure, it moves the gut-but if the nausea’s coming from the brainstem’s dopamine receptors, you’re just pouring water on a gas fire.

And don’t even get me started on droperidol. That’s not a treatment, that’s a liability with a prescription pad.

Scopolamine patches for vestibular nausea? Brilliant. Why isn’t this in every pain clinic’s starter kit?

Brian Furnell

December 22, 2025 AT 22:36While I appreciate the pragmatic, evidence-based approach outlined here, I must emphasize that the neuropharmacological underpinnings of opioid-induced nausea (OINV) are multifactorial: mu-opioid receptor agonism at the area postrema, vagal afferent modulation, and delayed gastric emptying are all implicated in the emetogenic cascade.

Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic variability among patients-particularly in CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 metabolism-can significantly alter both opioid and antiemetic efficacy, rendering even 'targeted' interventions suboptimal in certain subpopulations.

Thus, while the 'wait-and-see' strategy is reasonable, it should be paired with pharmacogenomic screening in high-risk cohorts, particularly those with a history of motion sickness or prior adverse reactions to 5-HT3 antagonists.

Hannah Taylor

December 23, 2025 AT 21:47ok so like… are you saying the government is hiding the truth about opioids??

why do they make us take these drugs if they just make us puke??

and why is ondansetron so expensive??

my cousin took it and then her heart started acting weird…

they dont want us to know the real side effects!!

Southern NH Pagan Pride

December 24, 2025 AT 23:19Let’s be real: Big Pharma pushed routine antiemetic prophylaxis because it increased prescribing volume and created dependency on their branded drugs. Ondansetron? Palonosetron? They’re not magic-they’re profit centers.

The real solution? Reduce opioid use entirely. Why are we even prescribing these in the first place? Chronic pain is a symptom, not a disease. We’re medicating symptoms instead of treating root causes-physical therapy, mental health support, nutrition.

And don’t get me started on ginger supplements. They’ve been used for millennia. Why do we need a $120 prescription when a root from a grocery store works?

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 25, 2025 AT 12:34This is one of the most clinically sound summaries I have encountered on the subject in recent years. The emphasis on symptom-driven rather than prophylactic intervention aligns precisely with contemporary guidelines from the American Pain Society and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

Furthermore, the recognition of opioid rotation as a therapeutic strategy-rather than a last resort-is both evidence-based and patient-centered. I will be incorporating this algorithm into my institutional protocols immediately.

Thank you for the clarity and precision.

Sandy Crux

December 25, 2025 AT 13:28Of course you’re going to say 'don’t prescribe antiemetics upfront'-because that’s what the pharmaceutical-industrial complex wants you to believe. They don’t want you to know that ondansetron’s QT prolongation risk is 17 times higher than what’s listed in the package insert.

And you mention 'tolerance in 3–7 days'-but what about the patients who never develop it? What about the elderly? The frail? The ones who end up in the ER with torsades?

It’s convenient to pretend this is simple. It’s not. It’s a minefield.

And ginger? Please. That’s the same logic that says 'vitamin C cures colds.' You’re not treating-you’re placebo-ing.

Jon Paramore

December 26, 2025 AT 05:28Correct. No prophylaxis. Wait. Assess. Match mechanism to drug.

Ondansetron for central nausea. Scopolamine for vertigo. Meclizine for elderly. Avoid droperidol unless you’re in the ER with a screaming patient and no other options.

Tolerance develops fast. Most don’t need it. Don’t overprescribe. Done.

Swapneel Mehta

December 27, 2025 AT 14:44This is so helpful. I’ve seen so many patients stop opioids just because of nausea, even when the pain relief was life-changing. The idea that it usually fades in a week is reassuring. I’ll definitely tell my patients that upfront now.

Also, the point about rotating opioids? Huge. I had a patient who couldn’t tolerate oxycodone at all, but switched to morphine and had zero nausea. Game-changer.

Thanks for breaking this down without the fluff.

Stacey Smith

December 28, 2025 AT 09:15Why are we even talking about this? Opioids are dangerous and should be banned. Stop enabling addiction with fancy antiemetic algorithms. Just say no.

Real Americans don’t need opioids. We have work ethic. We have willpower.

Stop coddling people who can’t handle a little discomfort. That’s what made this country great.

Ben Warren

December 30, 2025 AT 06:50While the author presents a superficially plausible algorithm, the underlying assumption-that opioid-induced nausea is a benign, self-limiting phenomenon-is dangerously reductive. The normalization of opioid use in chronic non-cancer pain has created a public health catastrophe, and the medical community’s focus on pharmacological mitigation strategies merely serves to perpetuate this epidemic.

The data on tolerance is cherry-picked: studies show that in patients on long-term opioids, nausea may subside temporarily, but gastrointestinal dysmotility and visceral hypersensitivity persist, contributing to chronic functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Furthermore, the suggestion that ginger or acupressure bands are viable adjuncts is not merely unscientific-it is an insult to the clinical rigor required in pain management. These are not therapies; they are distractions from the core failure of the opioid paradigm.

Until we address the systemic overprescribing, the institutional inertia, and the pharmaceutical lobbying that underpins this entire framework, no algorithm will save us from ourselves.

Theo Newbold

December 30, 2025 AT 18:59So you’re saying we shouldn’t give antiemetics unless the patient is actually nauseated? Shocking.

Let me guess-next you’ll say we shouldn’t give insulin until blood sugar is over 300, or antibiotics until the fever hits 103.

Prevention is medicine. Waiting until someone’s vomiting in the hallway is not a strategy-it’s negligence.

And you call this 'evidence-based'? The Cochrane review you cited included three studies with a total of 147 patients. That’s not science. That’s a suggestion.

Where’s the RCT with 10,000 patients? Where’s the long-term safety data? Where’s the funding?

Jerry Peterson

January 1, 2026 AT 04:04My grandma took oxycodone after her hip surgery and got so sick she almost quit. We tried ginger tea and Sea-Bands-she said it helped more than the Zofran. I’m glad someone’s finally saying this stuff out loud.

Also, the part about switching opioids? My uncle went from oxymorphone to tapentadol and suddenly could eat again. No drama. No side effects.

Just common sense. Why isn’t this taught in med school?

Meina Taiwo

January 2, 2026 AT 13:14Simple and clear. No fluff. Nausea fades. Don’t overmedicate. Pick the right drug for the right symptom. Rotate if needed. Natural options help. Done.

Thank you.